Dowagiac Days

#12 in the series, "A Legacy of Stories." Written by my dad, Forest Jordan

(Read about A Legacy of Stories, here.)

They lived in a small house that stood far back from the road and hidden among trees and bushes - a man, wife and two sons. They were gentle people, somewhat shy, as if feeling they occupied a humble place in the world.

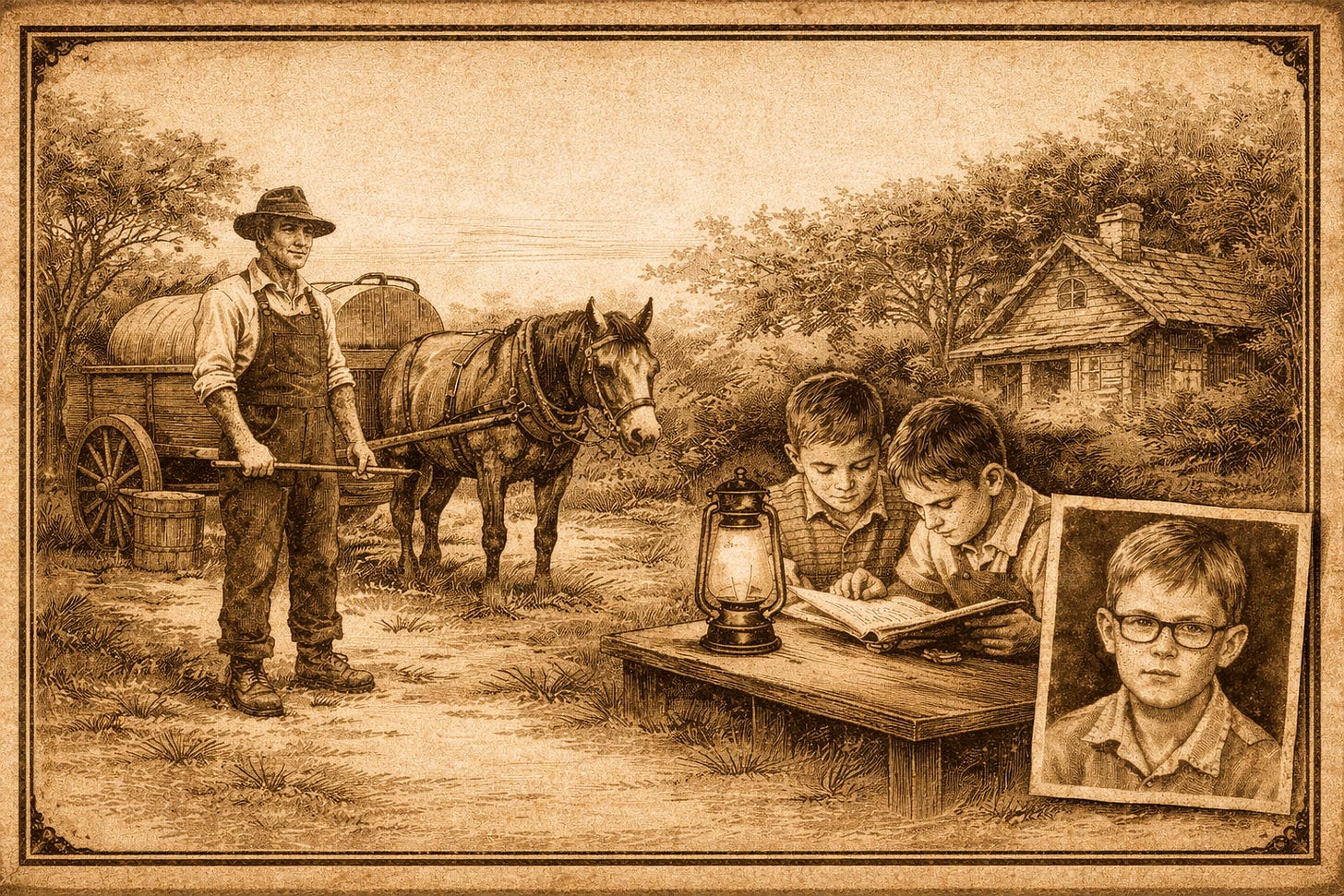

The father’s name was Dan. He serviced privies of which there were more than a few in this small town back in the thirties. An ancient horse pulled Dan’s wagon which held a large tank and he worked with the longest dipper you have ever seen.

No need to go further into the job. Suffice it to say he had no competitors.

The boys were neat and quiet. They bore the slings and arrows of their crueler schoolmates, though most of us treated them well enough. But lacking the sort of consideration that comes with maturity, we privately considered them lower caste.

All this was brought to mind recently when I came across a snapshot of my Sunday school class of 1937. Sitting cross-legged among us on the church lawn was Ernie, Dan’s younger son and a schoolmate of mine. He had pale skin, colorless except for freckles. It was a nice enough face, though somewhat pinched. It matched his thin undersized body, as if he could use more to eat. He was squinting into the camera; Ernie squinted all the time, as if he needed eyeglasses. You just had to know the family was very poor, yet the boys were always presentable and well mannered. Their mother must have been a remarkable person. Perhaps they had kind neighbors. Ernie and his brother, Robert, were excellent students. I remember studying with Ernie once at his home. We worked by gaslight.

I looked long at the photo. I tried to put myself in Ernie’s shoes. What must it have been like to know you were looked down upon because of your father’s work and because you were poor. And yet this did not sour the boys. They were likeable as was their father. I lost track of the family after school, but I think the boys must have done well. I hope so.

A note from me, Tom, about this short tale: As I read this, I’m struck by the strong strain of humility running through the piece. My dad was always attentive to the overlooked. In this story, as in life, he notices the details most people pass by: a boy’s squint, the thinness of a body, the cleanliness of clothes that must have been hard-won, the glow of gaslight during a study session. These aren’t decorative details; they’re evidence. He uses them to restore humanity to people who were casually diminished by circumstance and by the social blindness of others. Also, my dad doesn’t pretend innocence about childhood cruelty—he admits to it plainly, without excuse. That willingness to acknowledge moral failure, even decades later, suggests that he believed reflection mattered, and that growth didn’t erase responsibility.

What’s especially telling is his restraint. He never condemns outright, never moralizes, never turns Dan or his sons into symbols. Instead, he grants them something rarer: quiet respect. The father is “likeable.” The boys are “presentable and well mannered.” Their mother is “remarkable.” These are modest words, but they carry weight because they’re earned, not proclaimed.

Reading this, I’m reminded of how my father was someone who valued decency over status, kindness over cleverness, and understanding over judgment. He believed that character reveals itself not in what a person does for a living, but in how they bear it—and in how they treat others while doing so.